Pharaoh and Son – or daughter? An everlasting bond.

By Virginia Martos Armenteros

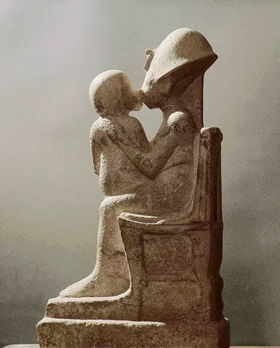

Egyptian Museum Cairo, “Pharaoh Akhenaten kisses his daughter”, Egypt Museum Cairo. Recovered from https://egypt-museum.com/post/188509076786/akhenaten-kissing-his-daughter.

Happy Father’s Day to all! Surely most fathers will be spending today relaxing with their families: having brunch with those near and dear, or reading special postcards, emails, or texts from those children who are far away. Maybe even appreciating the wonderful macaroni necklaces those very little ones have bestowed upon papa – or grandpa. In Ancient Egypt, however, the ways parents bonded with their children were a bit different…

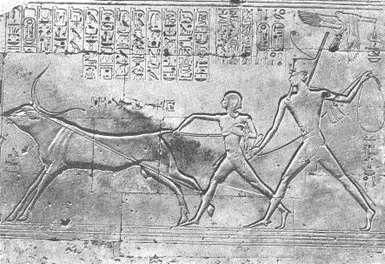

Ahmed Ebied, “King Seti I assisted by his son lassoing a sacrificial bull”, Abydos Temple. Recovered from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Fig-43-King-Seti-I-assisted-by-his-son-lassoing-a-sacrificial-bull-northern-wall-of_fig13_306014684.

Gods, Dads & Triads: The famous divine father and son duo, Osiris and Horus. Being a parent is no easy task these days, nor was it in Ancient Egypt. But sometimes being a son or daughter was even harder – especially when you have to avenge your dad’s murder! Let me take you through one of the greatest father-son stories in Egyptian mythology. The nuclear family was a key aspect of ancient Egyptian society. So important that even the gods had father-son and father-daughter relationships. Many divinities were organized in groupings (similar to families) known as triads. These consisted of a father, mother, and child. You can usually tell the child as he is depicted sucking his finger (as in the beautiful statue below).

Rogers Fund, “Triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus”, The Metropolitan Art Museum. Recovered from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/546178.

It is within these triads we find one of the most famous paternal-filial duos in the history of Ancient Egypt: the gods Osiris and Horus. Osiris is the god we today associate with the afterlife, but in mythology is portrayed as the first great king of Egypt. A fine fellow everyone loved and respected. Unfortunately, Osiris was murdered at the hands of his brother Seth, who wanted his title. Isis, the wife and sister of Osiris, stricken with grief, travelled all the deserts of Egypt collecting the different body parts of Osiris that Seth had scattered throughout the land of the Nile. She found all but one (the naughty bit – eaten by a Nile fish). Thanks to her magical powers, Isis was able to bring Osiris back to life and through an extra spell or two become pregnant with Horus, the falcon god and a great son indeed. Once Horus became an adult, he rose up to avenge his father’s death. He challenged Seth to a duel to decide who would be the new king of Egypt. After many “contendings” (in other words, rounds of battle, one in which Horus even lost an eye), Horus prevailed – and won back the throne that had been taken from his father. He became the king of Egypt on Earth, while dad Osiris ruled the Underworld. What a wonderful story demonstrating a son’s powerful love for his father – and successful mission to avenge his murder! From father to son: parenthood and the throne of Egypt. Fortunately, not all father-son relationships in Ancient Egypt are as dramatic as that. For the ancient Egyptians, sons, and daughters were a blessing, though not for the reasons you are thinking. Children were often referred to as “the staff of their father’s old age”. They were designated to assist him in the performance of his duties and eventually succeed him.

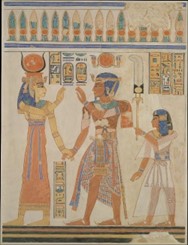

Nina de Garis Davies, “Ramesses III and Prince Amenherkhepeshef before Hathor”, The Metropolitan Art Museum. Recovered from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548357.

The family in Ancient Egypt was patrilineal, in other words, based on family relations through the father’s line. He bequeathed his name, his privileges, and position within a clan or class to his sons and daughters. You see this best in how the Ancient Egyptian monarchy functioned. Honouring the tradition of the myth discussed above, the kingship was transferred from the “Osiris” (the dead king) to the “Living Horus” (his successor). In other words, once the king died, it was his son who took his place and occupied the throne of Egypt.

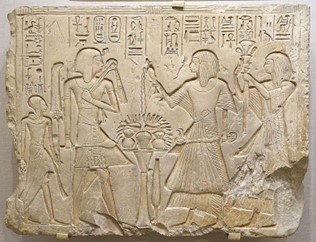

Daderot, “Seti I and his son, the future Ramesses the Great”, Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago. Recovered from https://fathom.lib.uchicago.edu/2/21701778/.

Let’s go fishing together in the afterlife: Father and son tomb of Mekhu and Sabni. The paternal-filial relationships in Ancient Egypt were not one-way. Just like today, fathers took care of the sons during their youth and early life, while the sons had to ensure the care of their father in his old age and at death. Children in Ancient Egypt were considered a blessing not only for the help and support they provided during life, but also because they represented the guarantee of a good burial. This above all things was something that would surely help a parent sleep well at night, both in this life and the next. For ancient Egyptians, having a son or daughter to oversee your burial created peace of mind, as it ensured a successful journey to the Afterlife.

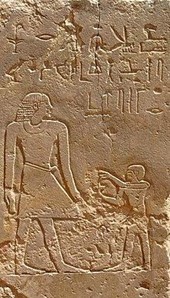

Olaf Tausch, “Figure of Sabni at the entrance of this tomb”, Qubbet el-Hawa Mechu Sabni. Recovered from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabni#/media/File:Qubbet_el-Hawa_Mechu_Sabni_05.JPG.

Way up in the hills of Elephantine across the river from Aswan city, there is a fascinating family tomb of Old Kingdom officials. It was built by a loving son Sabni for his dad, Mekhu. Mekhu and Sabni were governors (nomarchs) at the end of the 6th Dynasty during the reign of Pepi II (2278-2247 BC). When Mekhu passed away, his son Sabni not only took it upon himself to go down south to Nubia and collect his father’s body. He brought it home to Upper Egypt giving him a proper burial in a spacious tomb carved in stone, with all the nice things dad loved (scenes of delicious offerings, dedications and pleasant activities) to ensure a happy journey to the Duat. The peculiarity of this tomb is that after the completion of Mekhu’s burial, new rooms were added to accommodate other members of the family, including Sabni himself. In such a way, Sabni ensured father and son could enjoy a fine afterlife together.

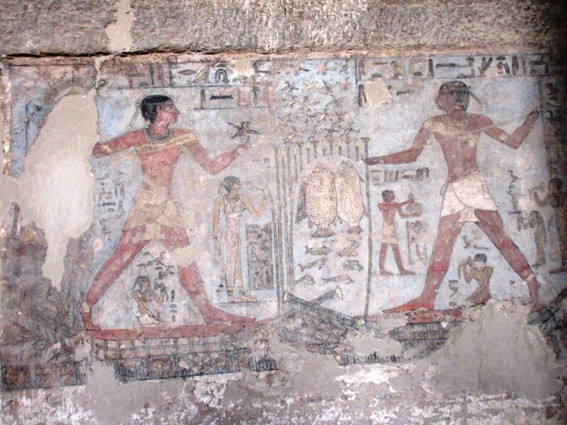

Mekhu and son Sabni fishing together in the afterlife, from tombs QH 25 and 26 at Qubbet el Hawa photo by L. Ranieri Roy.

This tomb is decorated with various scenes of the activities that father and son carried out in life. It seems that going fishing is something that all fathers have loved since time immemorial. Senenmut: Tutor and substitute dad for Hatshepsut’s daughter In Ancient Egypt, a father was not only responsible for providing care, a name, and a job for his children, he also had a vital role in their education. So much so that in 2220 B.C., the vizier Ptah-Hotep wrote a set of instructions that fathers should follow in order to achieve good parenting:

When a son receives instruction from his father, there is no mistake in all his plans. Instruct your son to be a docile man whose wisdom is pleasing to the great. Let him direct his mouth according to what he has been told; in the docility of a son his wisdom is discovered. His conduct is perfect, while error drags down the unlearned. Tomorrow, knowledge will support him, while the ignorant will be destroyed.

The beautiful block statues of Senenmut, Hatshepsut’s key advisor, architect, and BFF (if not lover), gives us a window into a rather non-traditional father and teacher relationship. Hatshepsut had lost her husband (King Thutmosis II) early in life, and was raising her daughter, Neferure, by herself. She was fortunate that close advisor Senenmut stepped up to the plate. He became the child’s protector and second tutor. While this is not the only case of someone stewarding a young royal child in Ancient Egypt, the numerous statues that exist of the two depict an intimacy that is quite remarkable. Many of them capture what appears to be a very close and affectionate relationship that went far beyond the typical teacher-pupil relationship. He clearly loved Neferure as his own.

Captmondo, “Block statue of the courtier Senenmut holding the princess Neferure in his arms”, British Museum. Recovered from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neferure#/media/File:BlockStatueOfSenenmutAndNeferura-LeftProfile-BritishMuseum-August19-08.jpg.

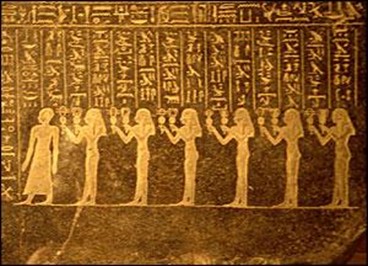

What about father-daughter relationships? Were the relationships that fathers had with their sons different, better, or closer than the ones they had with their daughters? Not at all! Just look at the many representations of Akhenaten with his daughters, and you will know how tender and loving it could be. There is another wonderful example we find on a statue base of an official from the early Ptolemaic period (4th century BCE). Djedhor, the chief guardian of the Sacred Falcon, is represented on one side with all his sons, and, on the other side (in equal measure), with all his daughters. This simple decoration shows how Djedhor’s relationship with his daughters was just as special as his relationship with his sons!

University of Chicago, “Djedhor and his daughters”, Oriental Institute. Recovered from https://fathom.lib.uchicago.edu/2/21701778/.

While Father’s Day may not have existed in Ancient Egypt, this civilization has left us so much beautiful art, reliefs, and statuary showing just how special father-child relationships were. So much so, that they transcended life itself! But today is not the time to think about the Hereafter. Enjoy celebrating with your loved ones – and be sure to give your father a big hug!

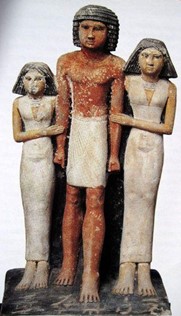

Selim Hassan, “Painted limestone standing triad of Mersuankh with two daughters”, Grand Egyptian Museum. Recovered from http://giza.fas.harvard.edu/objects/54828/full/.