By Laura Ranieri Roy, Egyptologist

Modern Egyptians, like many of us, have a serious sweet tooth. But did you know the ancients did too? 3,500 years ago, of course, there was no refined sugar to rot their teeth—just sand to wear them down. But luscious cakes and desserts made with wholesome honey, and fresh dates were in abundance!.

One of the most famous ancient Egyptian desserts—and possibly the very first recipe ever recorded—comes from the tomb of a man named Rekhmire. His tiger nut cones are carved and painted on the walls of his spectacular Theban tomb (TT100), complete with captions that describe the process step by step (for cooks in the afterlife, we presume!).

In this article, I’ll share this simple, oh-so-tasty recipe and a brilliant modern interpretation you can try in your own kitchen (scroll way down). But first, we’ll journey into Rekhmire’s life and remarkable tomb—uncovering some of the most fascinating facts about this powerful vizier, his career, and his mysterious fate.

Rekhmire the Vizier: A Man of Power and Mystery

Rekhmire was far more than a dessert aficionado. He was a Vizier of Egypt—Pharaoh’s number two man—under both Thutmose III and Amenhotep II at the height of the New Kingdom. His duties spanned everything from taxation and foreign diplomacy to supervising building projects and artisans.

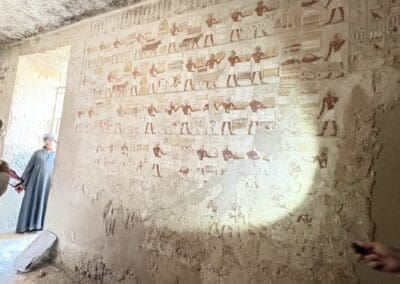

And yet, despite his power, Rekhmire’s end remains mysterious. His tomb, one of the largest and most beautifully decorated in Luxor’s Valley of the Nobles (at Sheikh Abd el-Qurna), contains no burial shaft. His body has never been found. Was he disgraced? Erased from memory? These mysteries live on in the colorful corridors of TT100. And yes, you CAN visit this tomb – as my tours sometimes do (though it is a bit of a hike).

Rekhmire’s Tomb: An Abundance of Fascinating Insights

Step inside TT100, and you’ll find yourself immersed in one of the most vivid windows into life and power in New Kingdom Egypt. Rekhmire wasn’t just any official—he was vizier under two of Egypt’s mightiest kings, Thutmose III and Amenhotep II, serving at a time when the empire stretched from the 4th cataract deep in Nubia to the mouth of the Euphrates. His tomb reflects this grandeur, but also hides tantalizing mysteries.

For one thing, although TT100 is vast and beautifully decorated, it contains no burial shaft or body. Scholars still debate whether it was ever meant to be a true burial place, or if Rekhmire’s remains were laid elsewhere. This absence, combined with the fact that many of his images and those of his family were later chiseled out or painted over in red, suggests he may have fallen out of favour?—perhaps denied the burial rites normally due a vizier?

Architecturally, the T-shaped tomb chapel impresses with its long corridor that stretches 27 meters, the ceiling gradually rising from just over 3 meters to more than 8 meters. The effect is ceremonial, leading you deeper into Rekhmire’s world. And what a world it is: a significant portion of the walls are still covered with well-preserved, colourful scenes that reveal both statecraft, craftsmanship, and daily life.

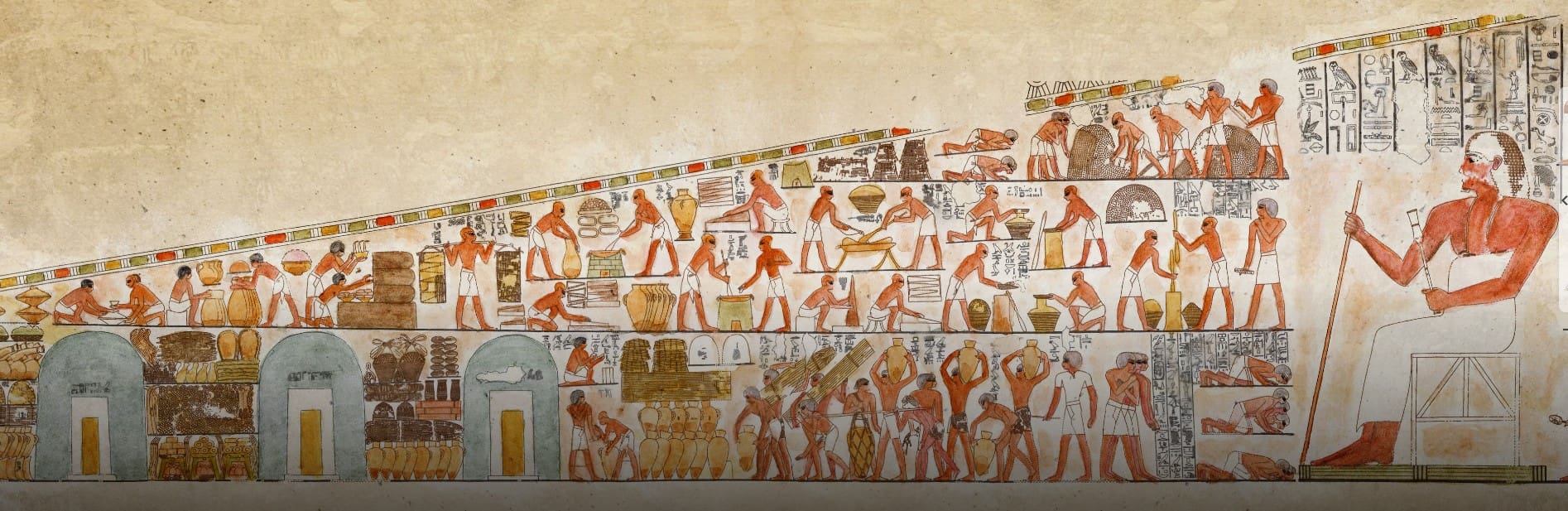

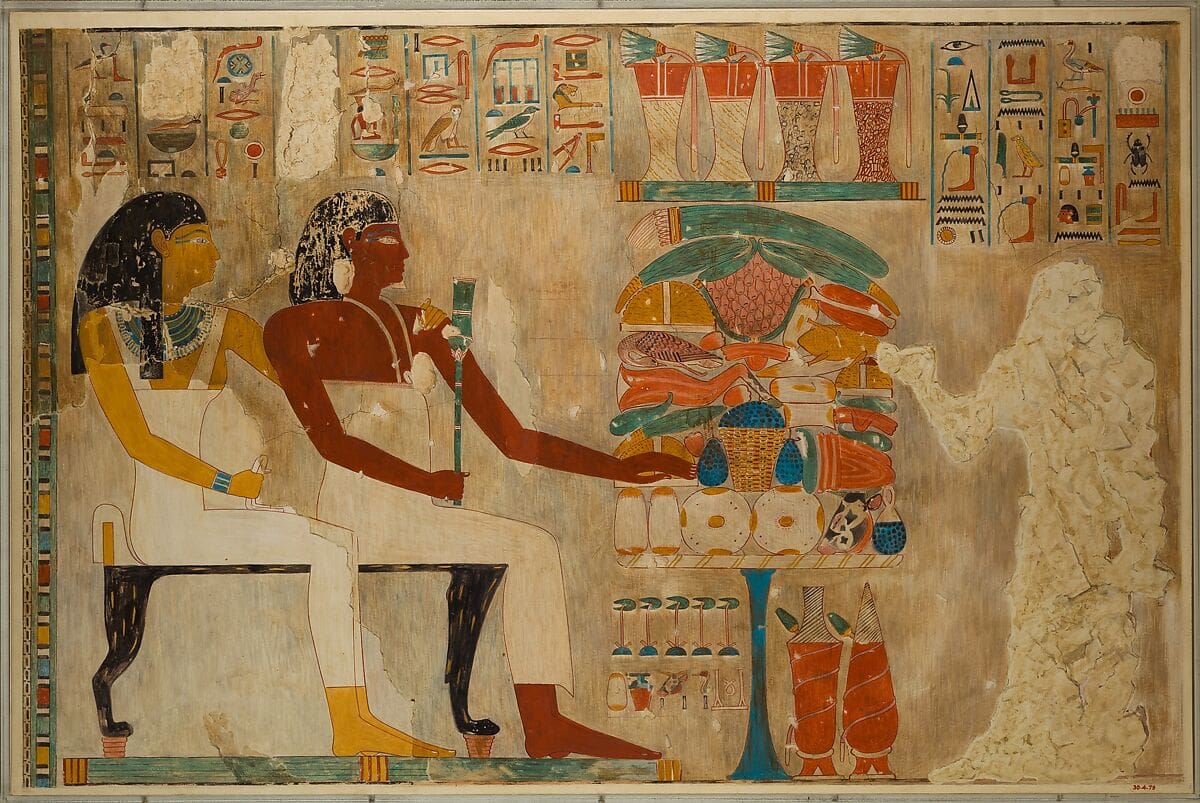

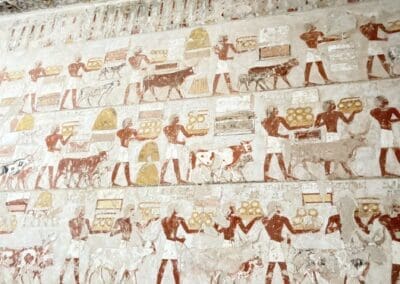

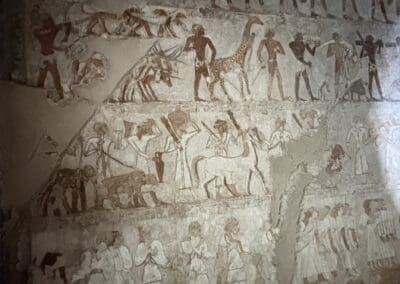

Here, we see Rekhmire presiding over tribute from foreign lands: giraffes, elephants, incense trees, ivory, and even a baby elephant and a bear are marched before him, brought by envoys from Nubia, Punt, and Keftiu (ancient Crete).

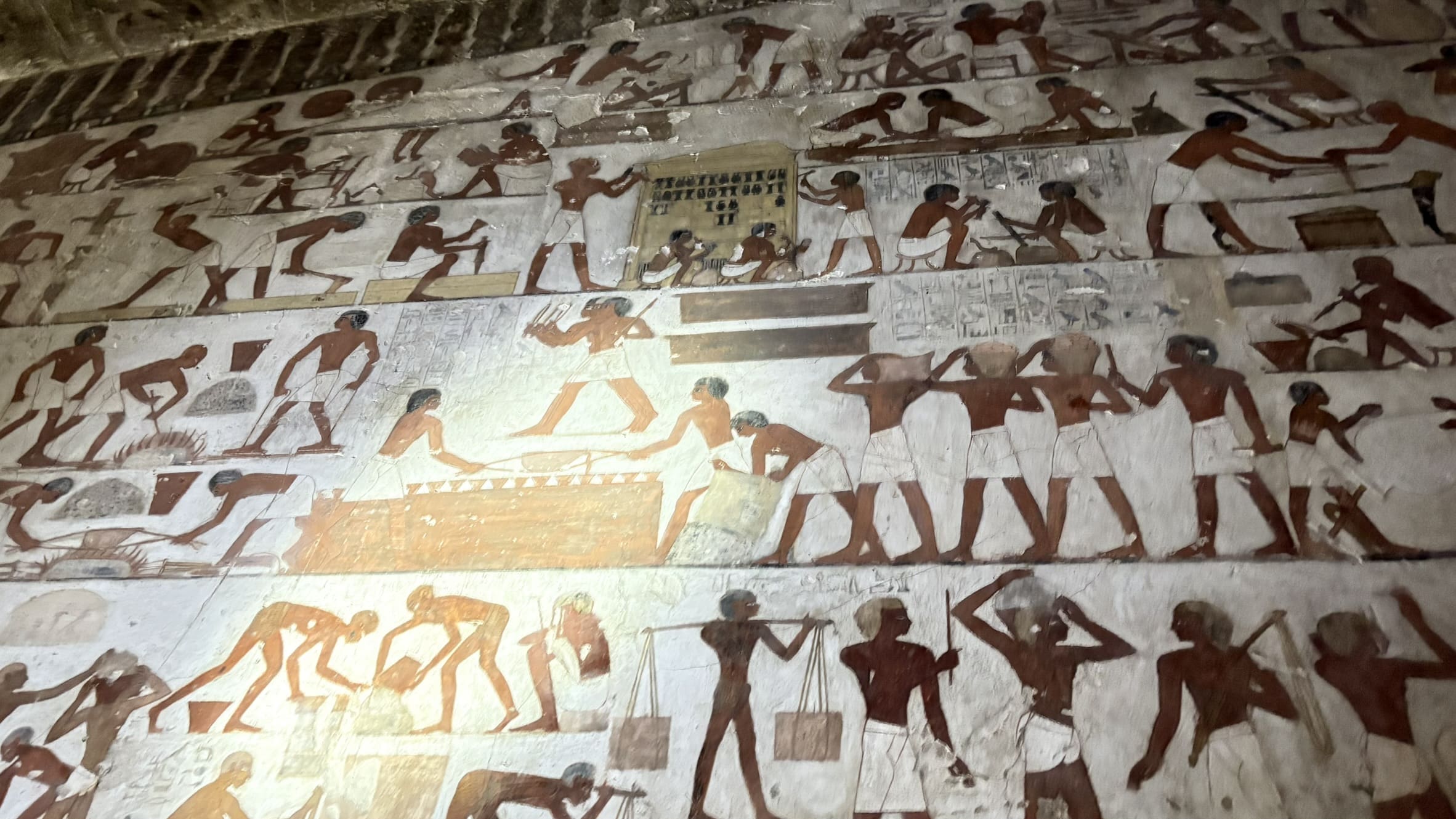

Elsewhere, artisans are shown at work in meticulous detail—carpenters, metalworkers, leatherworkers, jewelers, stonecutters—each plying their trade with tools so precise that Egyptologists can reconstruct their techniques.You can see some of these craftsmen where not Egyptian but Nubian – and even Syrian – with blond hair and blue eyes. You can see them working on colossal statues and even enormous gilded funerary shrines – very similar to the ones Carter found in Tutankhamun’s tomb!

Amid these depictions of power and production, Rekhmire also allowed space for more personal pleasures. The walls show his lush gardens filled with trees and a central pool, offering a rare glimpse of elite estate life. There are also joyous scenes of grape harvesting and winemaking, a reminder that Rekhmire, like many of Egypt’s elite, clearly relished good wine.

Perhaps the most remarkable text inscribed in TT100 is the “Installation of the Vizier”, a unique record that lays out his duties and moral obligations: to act with integrity, hear petitions from both the great and the small, and ensure fairness in all judgments. It is as much a manual of government ethics as a funerary inscription.

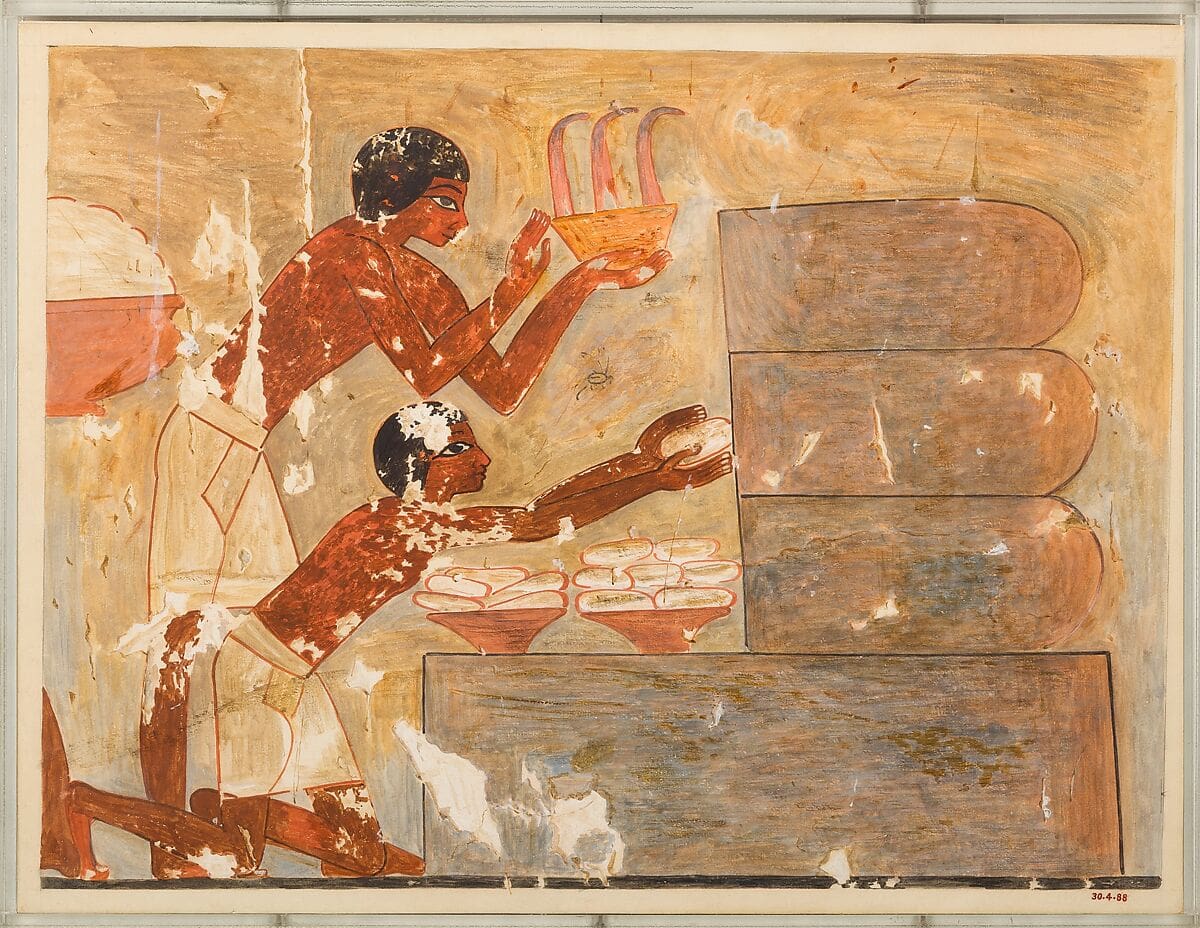

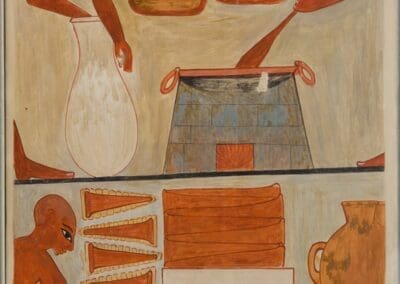

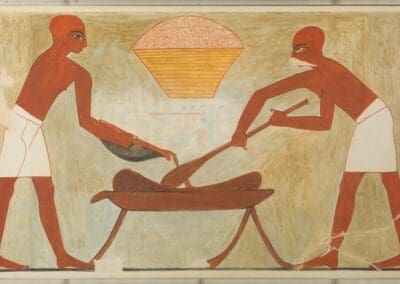

And then, of course, there is the sweetest detail of all: the famous tiger nut cake scenes. Step by step, the walls show figures grinding tiger nuts, mixing them with honey, shaping them into cones, and presenting them as offerings to the god Amun. The hieroglyphs instruct: “Pound the tiger nuts, sweeten with honey, form into cones to present to the god.”

More than sacred offerings, these were undoubtedly treats enjoyed by the living as well—rich, nutty, and delicious. No wonder Rekhmire wanted them in the afterlife!

Here is a “play-by-play of the tiger nut cone preparation scene:

- Grinding/Pounding stage

“Pound the tiger nuts (ḥbs šedja) with honey (bjt) and finely ground grain.”

→ The men are shown grinding tiger nuts with pestles, and the text literally instructs to “pound” or “beat” them. - Mixing stage

“Combine with sweet dates, make into a smooth paste.”

→ In the scene, assistants add honey and dates to the ground nuts in large bowls, mixing with wooden paddles. - Forming stage

“Shape into cones for the offerings.” (sḥtp n Imn — “to present to Amun”)

→ Figures are shown shaping small conical cakes, sometimes holding them aloft in baskets. - Baking/cooking stage

One caption reads something like: “Bake the cakes until ready, remove them from the fire.”

→ It’s debated whether the cones were baked, steamed, or dried, but the captions do suggest some heating process. - Final presentation

“Present before the god, that he may live by them forever.”

→ The finished cones are displayed on offering tables, emphasizing their dual role: sacred food for Amun and indulgence for Rekhmire in eternity.

Together, these scenes make TT100 one of the most fascinating of all the Valley of the Nobles tombs—a place where politics, power, pleasure, and pastry all come together.

Rekhmire’s Tiger Nut Cones – Ancient Recipe Brought to Life

Here’s a wonderful modern adaptation by Chef Signe Langford that stays close to the ancient treat:

Ingredients

- 10 pitted dates

- 2 cups tiger nut flour (find it online at Well.ca)

- ¼ cup honey

- ½ cup melted butter, ghee, or lard (butter works best)

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 350°F (175°C). Line a small baking sheet with parchment.

- Soak dates in just-boiled water for 15 minutes, then drain (keep the water).

- In a food processor, blend tiger nut flour, honey, butter, and softened dates into a dough. Add a spoon of date water if too dry.

- Pinch into 10 equal pieces, roll into cones, and place on the sheet.

- Bake about 20 minutes, until cone tips are golden.

- Cool slightly, drizzle with honey or date syrup, and enjoy!

Makes 10 cones.

A Vizier’s Legacy in Sweets and Stone

Rekhmire’s tomb is a treasure trove of art, politics, and daily life. From the pomp of foreign tribute to the humble sweetness of tiger nut cones, his afterlife abode preserves a vivid slice of New Kingdom Egypt.

So next time you crave dessert, why not bake like an ancient Egyptian? You’ll be tasting history—sweet, nutty, and 3,500 years old.