When we think of Ancient Egypt, towering pyramids, resplendently painted tombs, and majestic temples come to mind. And of course – the Nile! But beside the river, and beyond the grand stone monuments — thrived a lush and fragrant world of gardens, trees, flowers, and plants. Greenery and the gifts of mother nature played a surprisingly central role in daily life, religious practice, royal power, and dreams of the afterlife.

A Love Affair with Nature

In a land where the vast desert met the life-giving Nile, gardens and green spaces were not just beautiful—they were vital symbols of order, prosperity, and divine blessing. Everything was imbued with meaning, Egyptians believed that the perfect balance between chaos and harmony (what they called ma’at) could be reflected in cultivated landscapes. (And of course, they were obsessed with LIFE – not death – that’s why they wanted it to go on forever!)

Nebamun’s garden, Tomb-chapel of Nebamun, c.1350 B.C.E., 18th Dynasty, paint on plaster, 64 cm high, Thebes, Egypt © Trustees of the British Museum

Gardens provided shade, food, medicine, perfume, and spiritual symbolism. They were planted around temples, in private homes of the wealthy, and inside palace courtyards. Even the gods were believed to dwell in verdant, fragrant spaces. To create a garden was, in many ways, to imitate the paradise of creation itself.

What Ancient Egyptian Gardens Were Like

For the ancients, the perfect garden was a rectangular space, surrounded by mudbrick walls, with walkways flanking long pools of water filled with blue lotuses. Palm trees and sycamores rise along the edges, and date or fig trees offer shade. Carefully planted beds hold vegetables and fragrant herbs. These were the gardens of nobles and priests—sanctuaries of life and reflection.

Gardens could be functional, ornamental, or sacred. In temple gardens, priests grew papyrus, lotuses, and herbs for rituals. Palace gardens were more elaborate, used for pleasure, diplomacy, and showcasing wealth. Even modest homes might have small spaces with vines or herbs. And within every garden was a reflection of Egypt’s deepest beliefs—none more evident than in its symbolic plants.

Lotus and Papyrus: The Sacred Symbols

Lotus and Papyrus: The Sacred Symbols

Two plants held powerful, almost mythological, meaning in Ancient Egypt: the lotus and the papyrus.

The lotus, especially the blue lotus (Nymphaea caerulea), was associated with rebirth and the sun. It closed its petals at night and re-emerged in the morning sun, just as the soul was thought to rise after death. The lotus was linked to the god Nefertem, and scenes of lotuses blossoming are found in tombs, temples, and on perfume vessels.

The papyrus plant, on the other hand, was connected to Lower Egypt and symbolized life, writing, and civilization. Grown abundantly in the Nile Delta, its stalks were used to create the world’s first paper-like scrolls, as well as ropes, baskets, sandals, and even small boats.

Together, lotus (Upper Egypt) and papyrus (Lower Egypt) symbolized the unity of the two lands. They were often depicted tied together around the hieroglyph for union or shown embraced by gods crowning the pharaoh.

Trees: Sacred, Rare, and Imported

Egypt didn’t have a wide variety of native trees, but what it did have was cherished. Sycamore fig, date palm, tamarisk, persea, and acacia trees were valued for their shade, fruit, wood, and mythological connections.

The sycamore, for instance, was sacred to the goddess Hathor and often planted at tomb entrances. It was thought to offer the deceased nourishment and shelter in the afterlife.

Yet, some of the most prized trees weren’t native at all. The cedars of Lebanon were so valued for their strong, aromatic wood that the pharaohs of the Old and Middle Kingdoms mounted expeditions to Byblos (in modern-day Lebanon) to acquire them. These imported cedars were used for making luxurious furniture, elite coffins, and even the boats that ferried kings to their tombs.

The trade in exotic flora was so important it became a tool of diplomacy and empire-building—especially under one of Egypt’s most adventurous kings.

Thutmose III’s Botanical Treasures

Thutmose III’s Botanical Treasures

Pharaoh Thutmose III (1479–1425 BCE), sometimes called Egypt’s Napoleon, expanded Egypt’s empire to its greatest extent. But his love of conquest extended beyond gold and tribute. After a victorious campaign in Syria, he brought back not only prisoners and loot—but also foreign plants and trees.

At the Temple of Amun at Karnak, his “botanical garden” is immortalized in detailed carvings. The walls of the Festival Hall show carefully labeled images of plants, flowers, and trees from the Levant and other conquered territories. It’s an ancient version of a botanical archive—an emperor’s garden catalog chiseled in stone.

Though most of the plants have not been precisely identified, they reveal a desire to bring the exotic into the sacred space of Karnak—to celebrate the world’s bounty as gifts from the gods and proof of Egypt’s dominance..

Fruits, Vegetables, and Fragrance

Egyptians enjoyed a healthy and varied diet thanks to their fertile Nile Valley. Gardens and fields yielded onions, garlic, leeks, lettuce, cucumbers, lentils, chickpeas, and beans. Watermelons, dates, figs, and grapes were common, with dates and figs often dried for year-round use.

They also grew plants for oils, perfumes, and medicine. Henna, frankincense, myrrh, and lotus oil were prized for beauty and ritual.

And yes—flowers were everywhere! Bouquets were offered to gods and placed in tombs. Garlands of lotus, cornflowers, mandrakes, and poppies adorned the living and the dead. Wearing a flower on one’s head was not just a fashion choice—it was a spiritual and sensual delight.

Life After Death… With Plants

Life After Death… With Plants

In the Egyptian vision of the afterlife—the Field of Reeds (Aaru)—paradise looked a lot like an ideal Egyptian garden. Tomb scenes show the deceased tending fields, relaxing under trees, and boating through lotus ponds.

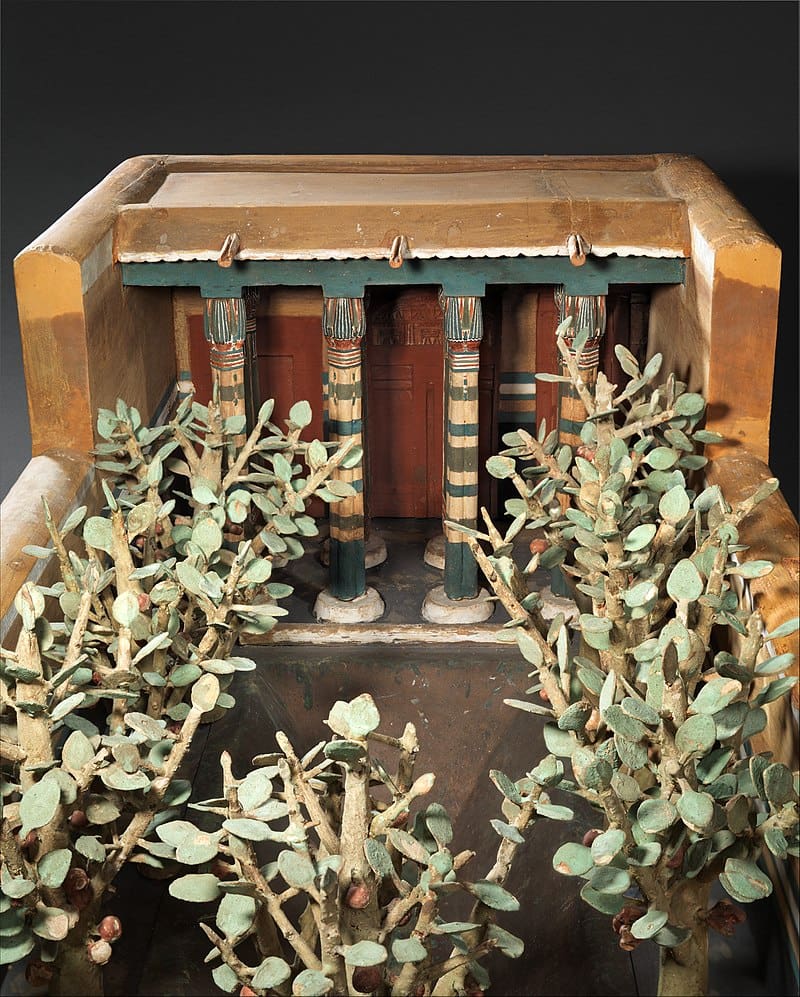

To ensure this eternal garden life, people were often buried with seeds, garlands, and wooden models of gardens. Some tombs included symbolic trees or painted garden pools. The sycamore, once again, played a starring role as the “Tree of Life” that fed and shaded the soul.

Even elaborate tomb goods like the golden shrines of Tutankhamun included floral motifs, and his mummy mask featured inlaid lapis lazuli lotus blossoms. The concept was clear: beauty, nature, and renewal belonged not only to this life—but the next.

Green Roots in Golden Soil

For the ancient Egyptians, plants were never just plants. Like so many things in the world of Ancient Egypt, they functioned on many levels. They were sacred symbols, markers of status, food and medicine, offerings to the gods, and essential ingredients in the journey from life to afterlife. The legacy of Egypt’s flora is still alive today—in the lotuses on temple walls, in the cedar coffins preserved in museums, and in the quiet reverence we feel walking through a desert oasis or a formal garden. And of course, many of the same wonderful trees & flowers– from the dom and date palm to the hibiscus and the pharaohs may have ruled in gold, but they were rooted in green!

May the great civilization of Egypt with its wonderful flora and fauna remain a perennial delight to all lovers of gardens and history and life – today and tomorrow!

Want to learn more?

Join us for Flora of the Pharaohs—a live lecture diving into the powerful role gardens, trees, and flowers played in Egyptian life, religion, and royalty. From lotus pools to cedar coffins, you’ll see how nature wasn’t just admired—it was worshipped.