By Laura Ranieri Roy

It was my extreme pleasure this May (though the displeasure of my feet, which trod more than 4 hours through this massive complex) to visit the great Vatican Museum in the Vatican City, Rome. What an embarrassment of riches it holds –priceless artistic jewels spanning millennia from the far reaches of the world.

The Vatican Museum, founded in 1506, is a vast and palatial labyrinth of rooms resplendent with artistic masterpieces of incalculable worth. 70,000 precious artifacts – 20,000 on display. And countless secrets lurking within its tangle of treasures.

One of the most fascinating series of galleries is the Gregorian Egyptian Museum, a series of nine rooms located in Belvedere Palace (Innocent VIII). The collection was created in the former 16th century apartment and retreat of Pius IV. Its founder was Pope Gregory XVI, ruling at a time of great excitement about everything Egyptian following the first decipherment of hieroglyphics. Pope Gregory was driven by a passion for learning. He ordered that all Egyptian and “Egyptianized” artifacts in the Pontifical states (and Roman antique markets, private villa collections etc.) be gathered together in a new museum.

The expert behind the museum’s formation was Barnabite Father Giuseppe Ungarelli. Ungarelli, its first curator, was himself an eminent Egyptologist and disciple of Ippolito Rosselini, (Champollion’s closest Italian colleague – and the father of Egyptology in Italy).

1834-36 Painting by Giuseppe Angelelli of the Franco Tuscan Egyptian expedition. Ippolito Rosselini (founder of Italian Egyptology, centre with the red beard, Champollion, seated centre, with striped shirt. They influenced Ungarelli, the first Vatican Egyptian museum curator.

My overall impressions? It is an exceptionally fine Egypt collection characterized by two things:

- Inspiration and aesthetic of the post Napoleonic expedition era – and the newly cracked hieroglyphic script (Champollion 1922). It is certainly apparent that there was a genuine desire to learn from the greatness of Egypt’s past.

- The riches of Roman Egypt: Both treasures brought back by the Emperors and “Egyptianized styled” objects and statuary fabricated in Italy.

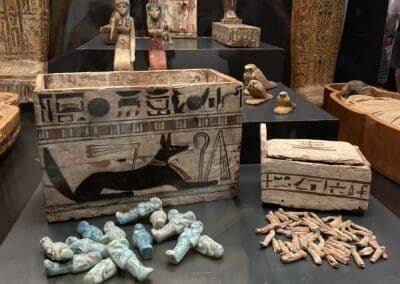

The Vatican Egyptian collection also happens to be a beautifully curated series of rooms in 19th century Egyptomania style, with so many important artifacts – from steles and coffins to magnificent statuary (particularly late and Greco Roman period) attractively displayed, well-lit, and intelligently explained.

Six Striking Highlights of the Gregorian Egyptian Museum at the Vatican Museums

1. Anubis, Roman Style

Anubis, the great Egyptian god of mummification and lord of the Necropolis retained his popularity through Roman times. He even got a special Roman rebrand, attired in a short Roman toga in this fine Parian marble statue from the 1st-2nd century CE. In Roman times, in fact, Anubis was merged with the Roman god Mercury. Here, he has a small solar disc on a crescent moon between his ears. In his right hand he holds a sistrum (an Egyptian musical instrument, a rattle associated with Hathor), while in the left he has the caduceus of Hermes, which was used to guide the souls in the Greek-Roman religion.

The statue found in Anzio at the Pamphij villa was donated to Pope Benedict XIV in 1749 and transferred to the Egyptian museum upon its opening in 1839.

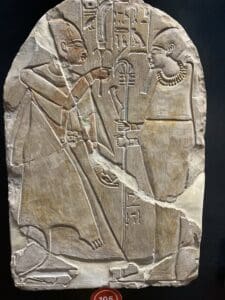

2. Two Steles for the God Ptah

I am personally fascinated by the god Ptah, the blue cap wearing craftsman god of Memphis. The artistry of these two dedication steles, one found in Memphis, and the other (fittingly) in the workman’s village of Deir el Medina is admirable.

Ptah was the god of the capital city Memphis, but also an important creation god who, it was said, created the universe by thinking and speaking it into being. Many Egyptian kings, queens and commoners, dedicated to Ptah seeking his blessing for Maat (harmony and balance) across the land, and certainly for life, health and prosperity. Notice how on the Memphis stele (right) he is shown carrying his was sceptre (power symbol) inside his shrine, “the white walls” of Memphis. Ptah is considered the very embodiment and spirit of Memphis.

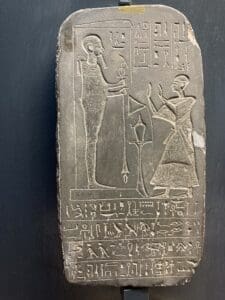

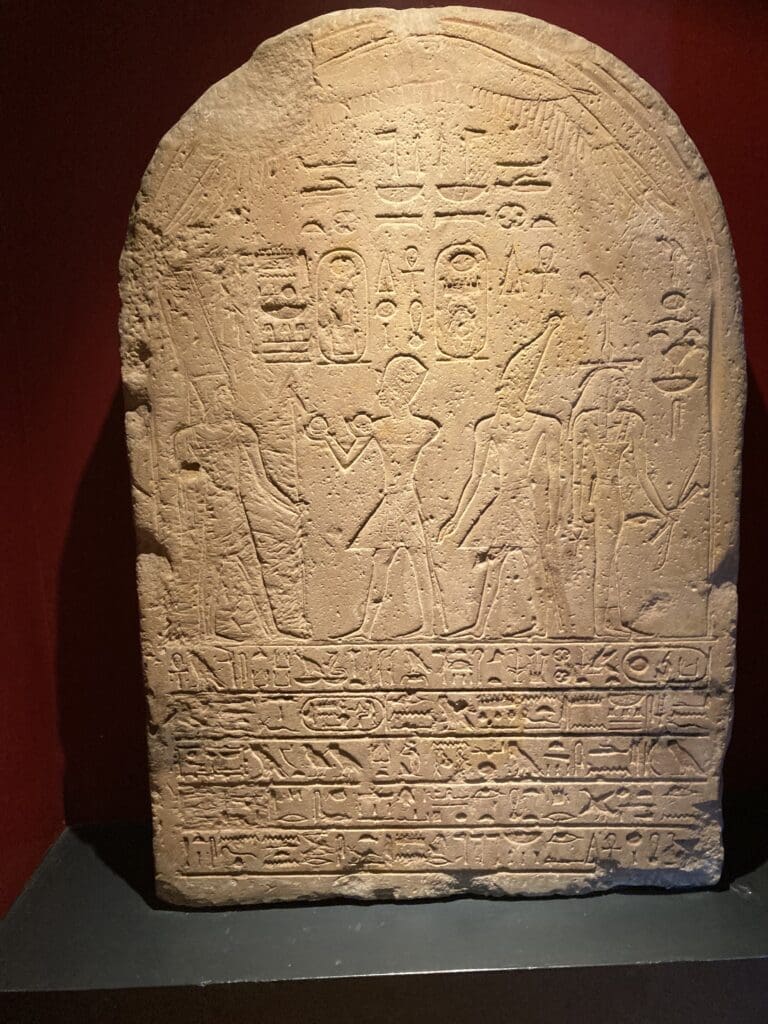

3. Stele of Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III, early 18th dynasty

Perhaps not the prettiest object but an important one. A sandstone stele once erected in Thebes showing Hatshepsut and her stepson/nephew as co-rulers during the early co-regency. That is, the brief seven years of rule before Hatshepsut assumed full power and the guise of a king. It was erected in Western Thebes to commemorate restoration and building works in the name of the great god Amun. Hatshepsut in the blue crown of lower Egypt brings offerings of nu vases (incense) to the god, followed by young Thutmosis III bearing the white crown of Upper Egypt. It entered the Vatican in 1819 apparently … but how did this important stele make its way to Rome?

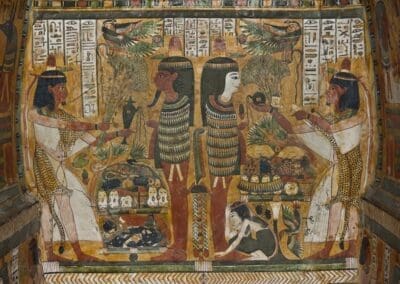

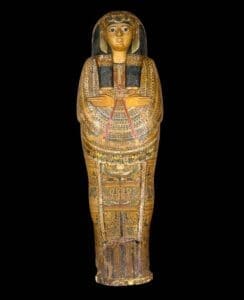

4. 22nd Dynasty Coffin of Djedmut (945-909 BCE)

It seems many Egyptian collections have their own “chantress of Amun” mummy and coffin dating to the late period. The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto (my hometown) certainly does. Many aristocratic women living in ancient Waset (Thebes/Luxor), in fact, had this job, singing and making music at Karnak. Djedmut, chantress of Amun’s mummy and coffin at the Vatican museum is especially fine, in its typical 22nd Dynasty yellow coffin style. In this later period of Egyptian history economic crisis led to the decline of the elaborate tomb and the rise of most beautiful coffin arts. The workman’s village we know as “Deir el Medina” closed at the end of the New Kingdom and many of the workers had “pivoted” their business from tomb building to creating beautiful coffins like this one. It bears all the stunning iconography and protective spells to keep the deceased lady safe en route to her glorious afterlife.

The coffin shown here is the outer coffin and there would have been an inner coffin in which the mummified body was placed.

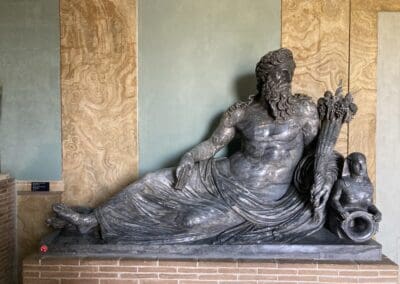

5. Statue of Osiris Antinous, early 2nd century CE – from Tivoli

The beautiful marble statue depicts a man named Antinous, a favourite and probable lover of the Emperor Hadrian who drowned in the Nile. It dates back to about 131-138 CE, discovered at Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli.

Grief-stricken, Hadrian deified his handsome Antinous and created a syncretic god merging him with the god of the afterlife, Osiris. So great was his love for Antinous, Hadrian also founded and named an Egyptian city, Antinopolis – and even tried to name a constellation after his beloved (an unsuccessful endeavour).

Note the typical left leg striding forward position of the statue, inspired by age old Egyptian iconography. Yet the work is unmistakably Roman by evidence of its features, Roman attire, and the somewhat fey, fluid and relaxed ‘sloped back’ pose.

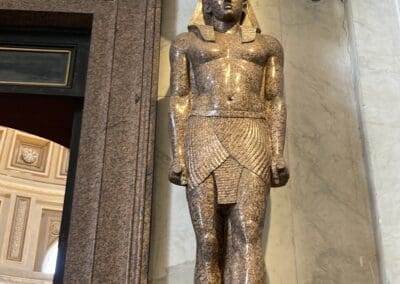

6. Statue of Queen Tiye – usurped by Ramses III for his mother Tuya

A true gem of the Vatican collection, this large granite statue was originally fashioned for Amenhotep III’s great Queen Tiye (18th dynasty Egypt), and stood in Kom el Hettan, his great mortuary temple. It certainly bears a strong resemblance to the statuary of Tiye that Dr. Sourouzion’s team is continuing to unearth at the Kom el Hettan site today. In the 19th dynasty, Ramses the Great usurped it, bringing the statue to his mortuary temple (the Ramesseum) where it was rededicated to Ramses own mother (and the wife of Seti), Tuya. On the left side of the statue pillar, we see a depiction of Ramses II’s sister (once thought to be daughter) Henutmire.

The beautiful work once graced Emperor Caligula’s “Gardens of Salust”. It was unearthed in the garden of Vigna Verospi and entered the museum in 1839.

In the immensity of the great Vatican museum (which is the size of a large village), the nine-room Gregorian Egyptian collection may get overlooked on a visit. Yet, it is a true jewel of the Vatican not to be missed… and stands out as one of the world’s great Egyptian collections.