By Laura Ranieri

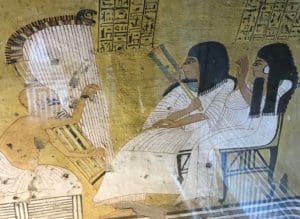

Tomb of Innerkhau TT359, Deir el Medina. (Innerkau and wife enjoy beautiful music in the afterlife, played by a blind harper) Photo by Laura Ranieri

As I wake up, grab my phone and scan another day of terrifying news headlines, spread by the dark forces of the ‘COVID-19 Crisis media’, my mind turns to Ancient Egypt.

If we were living during the times of Khufu, Hatshepsut or Ramses, along the beautiful banks of the Nile we’d never wake up to horror stories like this. There were no mass broadcasts about famine, disease and devastation. No country-wide hysteria and self-isolation bans. No mobilized troops of soldiers marching through the land with dire news of the many terrors to come… and how we must bolt our doors, close our businesses and shrink in fear. Of course, there was no Internet, TV radio or papers either.

Right or wrong, Egyptian rulers did not intrinsically believe in spreading bad news. They didn’t write it, depict it in their art… or engrave it for eternity on their magnificent monuments. Yes, there were plagues and famines from time to time, but they were not fueled, magnified and immortalized by kings, artists, messengers and scribes.

The ancients fervently believed in telling stories of a more empowering, inspiring kind. The powers that be felt it was essential in order to keep society in balance. They did this through magnificent statuary, great obelisks and pyramids aspiring sunwards … and temples and tomb reliefs designed to promote balance, truth and order.

‘It’s true to say they kept the message positive, says Dr. Ronald Leprohon, professor of Egyptology at the University of Toronto, “Essentially because the king could never be wrong!”

Maat, the goddess of order and balance embracing Ptah, the creator god of Memphis, Tomb of Tawosret, Valley of the Kings, Photo Laura Ranieri

Balance order and truth (MAAT) was important to kings and subjects

In Ancient Egypt balance, truth and order was called ‘MAAT’. It one of the most important concepts throughout the long 3000 year-old civilization, intrinsic to good kingship – and upholding it was the foundational role of Pharaoh. There was even a beautiful winged goddess of MAAT with a feather on her head, often seen protecting gods and kings. (see above with Ptah)

Thinking and speaking “good things” into being: an Egyptian creation story.

And speaking of positive thinking, one of the most popular and enduring Egyptian gods was Ptah, the craftsman god of Memphis, usually shown wearing a little skullcap and standing on a dais within his white-walled temple. In one of Egypt’s creation stories, Ptah was said to have created the entire universe by “thinking it and speaking it” into being. Sound familiar? Yes, the ideas behind “The Secret”, and its 1950’s predecessor “The Power of Positive Thinking” has been with us for many millennia… though often forgotten, and frequently overlooked.

Harmony between gods and kings

Statue of Sobek and Amenhotep III 1403 – 1365 BC Calcite

Here’s a delightful image above of an 18th Dynasty New Kingdom statue currently in the Luxor museum carved of beautiful creamy calcite. It depicts the great King Amenhotep III, arm in arm with the crocodile God, Sobek that ruled the Nile. What is the meaning? By erecting an image of harmonious unity between King and this Nile god for everyone to see, it was believed happy times for Egypt would follow. An excellent Nile flood, abundant crops and prosperity for all, with god and king in concert… or as the Egyptians may say, in MAAT. The propaganda machine behind the crown had an unwavering focus: to keep the minds of the populace focused on positive outcomes: strong kingship, benevolent gods… and life, health and prosperity for Egypt.

Containing the chaos

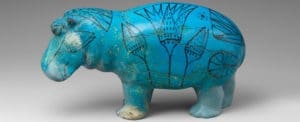

The triumph of order over chaos was another favourite theme. No wild beast, demon – let alone coronavirus) would be ever depicted inside a tomb or temple, unless slaughtered, speared or carefully contained. After all, it may let loose and wreak havoc on the world of the living, and dead. Take the favourite little blue faience hippo tomb statue (Middle Kingdom), lovingly called ‘William’, in the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. As cute as it is (and symbolic of the life giving Nile), the hippopotamus was known to be an extremely dangerous beast. Even as a tiny faience object it could prove a threat. In order to keep the tomb owner safe from its innate aggression, three of its legs had to be broken before he was put in the tomb. The Met has since restored the broken legs on the object.

William the hippo from the Met collection. Tomb object with three legs (now restored) deliberately broken, to control the hippos savage impulses in the tomb.

Unspeakable famine in the late Old Kingdom?

No doubt, the Egyptians certainly experienced devastating periods of plague, famine and disease. Images of such unspeakable times, as I say, are interestingly few and far between. However, we do have a famous relief from the time of King Unas in the 5th dynasty. The famous Unas famine relief from his pyramid causeway, depicts starving, emaciated Bedouins. A man and woman reach out to embrace one another in the throngs of despair. Another woman holds her head in anguish. The scene (larger than pictured with more suffering people) is quite disturbing, and often used as proof that famine was an important factor in the decline of the Old Kingdom. Nevertheless, it stands out as one of the few images of its kind in stone relief carving, documenting hard times and starvation. But we have no clear historic texts corroborating this famine at all. Was this depiction actually revealing a famine in Egypt… or just showing the suffering of Egypt’s enemies?

Sekhmet lion goddess statues served to ward off disease

So how did the Egyptians cope in times of famine and disease? Generally, they used the gods to keep these evil forces at bay. The ferocious Sekhmet, lioness goddess of war, famine and healing had the power to ward off disease. Interestingly, Pharaoh Amenhotep III in the 18th dynasty had a huge number, 710 large, imposing statues of Sekhmet carved in his royal workshops. He erected 600 of them in the Temple of Mut at Karnak. Does that mean a serious plague hit Egypt during his rule in the early 14th century BCE? His royal palace of Malkata after all, was located way out in a remote area of the western desert. And Akhenaten his son and the heretic successor, abandoned Waset (Thebes) altogether for a new capital in Middle Egypt.

Was the Amarna period actually sparked by the outbreak of plague? We may never know for sure.

Sekhmet in Temple of Mut, Karnak, Photo Laura Ranieri

Apart from a magnitude of Sekhmet statues, the reliefs, texts and stories are fairly mute. No mention of a plague in Amenhotep III’s reign. In fact, little is captured about period of disease and suffering in the long history of the ancient Egyptians. An exception might be the text from the Middle Kingdom “The Admonitions of Ipuwer” documenting ‘topsy turvy’ times of suffering and hardship, but this work was a literary one about a time long past, written in a text only readable by 2% of the native populace. One might also point to the boastful tomb autobiographies of local governors in the First Intermediate period, like Ankhtifi, who spoke of feeding the people in times of famine. But the purpose was not to broadcast about hardship, but rather to promote his own benevolence as a ruler who cared for his people in time of need.

So what can we learn from the ancient Egyptians that we can apply in these times of COVID-19 crisis?

Should we be erecting Sekhmets, instead of issuing masks? Reading “The Secret” instead of self- isolating?

No, probably not. However, this disease may be better endured, and conquered faster, if we all keep our thoughts, minds and hearts a bit more positive. The media needs to ease up a little on the horror stories and worst-case scenarios. Spread news on a ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ so the rampant fear and anxiety can subside a little. Even better, why not talk about something different for a change? Surely there must be other stories happening on the face of the planet to intrigue, inform and inspire than the latest dire predictions and COVID tragedies?

And maybe the odd Sekhmet statue wouldn’t be such a bad thing after all…